Fruit Bud Stages

In the Durham area on June 5th, McIntosh and Cortland apples both had some fruit at 3/4 inch size. Peaches: fruit size 3/4 inch. Blueberries: bloom almost over. Raspberries: bloom. Grapes had flower buds visible, shoots up to 18 inches long.

Apple Scab

The primary apple scab season is over for much of the southern part of New Hampshire. If you are using the NEWA system data from a site close to you, it should predict the end relatively accurately, provided that you had correctly entered the apple scab biofix (date when 50% of McIntosh buds are at green tip). The primary season ends with the next daytime rain, after all the spores have matured. Ten days after the end of primary season is an excellent time to do a final assessment (we often call it indexing) to see how well you did at managing the primary phase of the disease. All the lesions resulting from ascospore infection should be visible by that time. If you find no or very few lesions, you can relax scab management for the remainder of the season, and focus on bitter rot, flyspeck, sooty blotch and others. If you find a significant number of scab lesions, you may wish to make two back-to-back captan treatments to “burn out” those spore-producing lesions.

As a test, on June 2nd I looked at the NEWA data for Ossipee, and used April 14th as the date of green tip. That is two days later than we observed at the UNH Kingman farm in Madbury, and was my best guess for Ossipee. The model then predicted that all ascospores were mature June 1st, and primary season would end with the next daytime rain after June 1st.

Flyspeck and Sooty blotch of Apple

These “summer diseases” are caused by fungi that grow on the surface of the fruit, and on stems of LOTS of other hosts, including brambles, maples, wild apples & relatives. When the fungi grow on the surface of apples, they create cosmetic blemishes that lower the value of the fruit. So, many growers think about how to manage these fungi. They grow very slowly. The number of hours of leaf wetness after petal fall (I’ll abbreviate that & call it HLWAPF) is a critical measurement in managing the disease. Basically, we need 270 HLWAPF (if you are using old-style leaf wetness equipment) or 200 HLWAPF (of you are using the latest equipment) for each cycle of the fungus to grow and produce spores. We want to apply a fungicide that works on summer diseases at least once every cycle. In the early part of the year, we are usually focusing on apple scab, and often the fungicides we use also control summer diseases. We have the NEWA system to help monitor the weather. If you turn on your computer and visit the NEWA page for the weather station closest to you, it will predict where we are in the Sooty blotch/flyspeck cycle. First, it asks you to confirm the petal fall date for that site. For Durham/Madbury, petal fall on McIntosh was May 21-22. The model said that on June 2nd, we had accumulated 132 hours of leaf wetness after petal fall. If you enter when your last fungicide was, the model will predict the risk level you have for summer diseases. By the way, fungicides that are really effective on summer diseases include materials like Cabrio, Dithane, Flint, Manzate, Inspire, Penncozeb, Polyram, Pristine, Sovran and Topsin-M. Remember to rotate fungicides between activity groups, to reduce the risk of the fungi becoming resistant to the fungicides.

Summer diseases show up especially on varieties that are light, such as golden delicious and gingergold. The growth is less obvious on dark red fruit. A low incidence of these is probably not a problem on pick-your-own blocks.

Got Cherries and Peaches?

I haven’t said anything about cherries this year, because things were so busy on the other fruits we grow. Brown rot can be a serious problem on cherries and peaches, and we have two phases where we focus attention. One is the blossom and shoot phase, mostly passed now. The second phase is attacking the fruit. Fruit become very susceptible as they begin to ripen. A second risk factor (especially for cherries) is splitting and cracking. This opens up infection routes for the fungus to attack. Bird attack also threatens when the fruit turn color. Are your bird protection methods ready? The time will arrive before you know it.

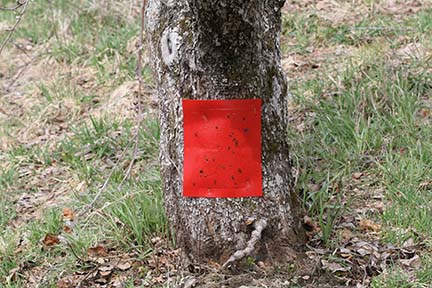

San Jose Scale

If you have a block of apples with SJS in them, you’ll probably want to consider making an insecticide application for the crawlers. The timing is important, and we use degree days to predict when the crawlers emerge. The NEWA system doesn’t currently include an SJS model, but it will compute degree days for you. You have to feed it information. It will need to know what base temperature you’re using [50F for SJS]. It will need to know the starting date (“biofix”). That’s when you captured your first SJS male in a sticky trap. Don’t use those traps? Then substitute the full bloom date. We expect SJS crawlers to appear 310DD after full bloom. Usually that is in mid to late June.

Plum Curculio Time

Plum curculio attack is heaviest from the time apples are 6mm in size, through the next 3 weeks or so. PC is abundant enough and active enough to reduce your apple crop by 75 to 100%, if you do nothing to control it. The early injury (see my photo) looks like tiny c-shaped scars. Soon, the eggs laid in those scars hatch, the larvae bore through the fruit, and the affected fruit usually drop to the ground.

Blueberries: Mummyberry Disease and Fruitworms

We had really good conditions for primary mummyberry infection this year. The risk of infecting the tiny green berries continues, and can be reduced by fungicide application. When bloom ends is the time to consider an insecticide for cherry fruitworm and cranberry fruitworm, both of which attack blueberries. Many plantings can go without this treatment, but some sites are prone to repeated attack. Both fruitworms are tiny caterpillars that bore inside the fruit. There are other caterpillars that eat the leaves, but most of them occur a little later in the year… usually July or August. One exception (on lowbush fields) is blueberry spanworm, which is feeding now.

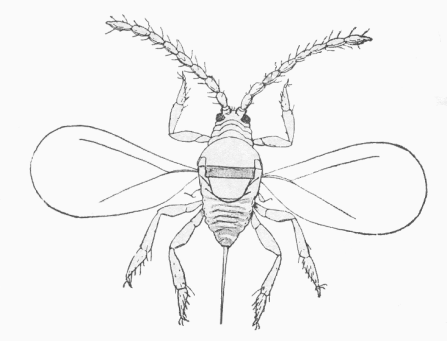

Strawberry Clipper in Blackberries

I covered this tiny weevil in the last issue, and pointed out that it was attacking Strawberries and Raspberries. Blackberries are in perfect stage for attack as I write this, and the process is the same. The weevils hit the unopened flower buds. Damage is typically worst at the edges of a bed, especially bordering woods.

Slime Mold — Yuck – In Strawberries

We have had so much cool, wet weather this year, I’m anticipating that we will see a significant amount of slime mold this year. I hope it will get drier and I’ll be wrong. But in case that’s not correct, I’ll show a photo. Strawberry fields seem especially good places to find slim mold. Maybe it is our use of mulch that helps keep the soil at the right temperature and moisture for slime mold. Whatever it is, slime mold doesn’t actually attack the plant… it just grows over it. Typically it appears as blackish stubble growing on a nice, healthy green plant. It changes/moves quickly. Customers do not like it, and the best advice I can give is to assure them that it is not dangerous, and there’s not much we can do to avoid it.

Alan T. Eaton

Extension Specialist

Integrated Pest Management

UNH Cooperative Extension programs and policies are consistent with pertinent Federal and State laws and regulations, and prohibits discrimination in its programs, activities and employment on the basis of race, color, national origin, gender, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, sex, sexual orientation, or veteran’s, marital or family status. New Hampshire counties cooperating.